|

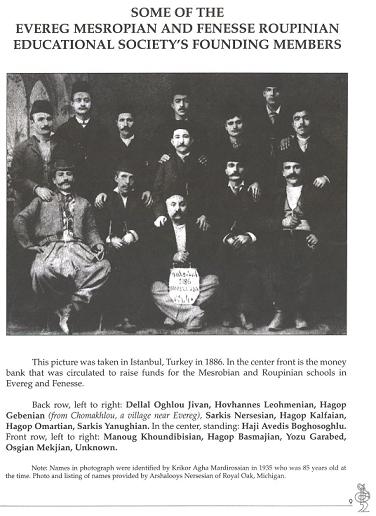

Mesrobian & Roupinian Societies, Founded 1878/1879

|

|

|

|

|

I made a trip to Develi in 2022 - Straddling Cappadocia and Cilicia lies the plains of the extinct volcano Mt. Erciyes

(Argaeus), prominent to those living it’s shadows. Modern day balloon rides in Cappadocia, a true resort area,

take advantage of these gorgeous sunrises over Mt. Erciyes for tourists to enjoy in an area studded with unusual rock formations

and Ancient Greek cave cities. These cave homes now house boutique hotels. My mother, Vart, whom I lost

in 2007, kept alive for me the memory for her parent’s ancestral town, the competing and neighboring towns of Evereg

and Fenesse, comprising the modern day Develi. After both her parents forcibly left the area as children in the early

20th century, a smattering of family members, including my grandfather, returned to visit the area to bring back relics.

It taught me that they must have had a continuing affection for the area and didn’t wish to let go. The stories

they would share was one of a diverse community of Armenians, Turks, and Greeks where relationships were amicable based on

interplays of agriculture and commerce. Political revolutionary rhetoric was mild here compared to other areas on the

Armenian Highlands likely based on relative respect and value. Nevertheless the area did not escape forced relocation

in 1915 when the central leadership changed the value equation. So goes the economics of genocide. Stories told,

wonderful if they were really true, is that some of the town’s sympathetic Turkish population hired private guards to

protect their Armenian neighbors leaving the towns to the borders of their vilayet (district) on their long journey to Syrian

deserts. Bandits, raiders, and lawlessness would have otherwise ensured that convoys would be attacked, looted, and

killed. I’m not sure it helped in the end but this sympathetic action demonstrated dissent in the Turkish populace

about the central government’s directives. Some Armenian survivors returned to the towns after the Great War ended and

chose to rebuild the community but the magic was gone. The last Armenian died in the community in 1964. By that time

the Armenian community had lost use of a main church and school, their second church had collapsed, and their markets all

gone. In 1968 as an act of final erasure, the Develi Armenian community’s cemetery was co-opted by the local municipality

to build a playground and religious center. Bones collected were sent to Istanbul’s Balıklı Armenian

Cemetery for a communal memorial. So our true Develi journey had actually begun in Istanbul’s Balıklı

Armenian Cemetery Evereg Fenesse memorial ten days before. Today we would be visiting Develi itself.

In

2000 the opportunity presented itself that my mother and I were able to visit historical Armenia. Develi was not on

that planned route but I paid a guide to take us to the town. As we approached the city at the time, my mother’s

eye filled with tears. Losing the location momentarily we went to a local police station for directions. They

were friendly, especially when I started discussing basturma and soujouk, dried meats which are a specialty of the area.

We found the Evereg church, now a mosque, which was in a state of renovation. My mother and I ran in and said prayers

and hymns among plaster and scaffolding. There was a fresco of possibly the Virgin Mary or a female saint on one of

the columns where the white plaster was peeling. And then we left. 30 minutes or so at sundown. The

visit never left me though.

I chose to tell the late 19th century story of how the two competing towns each hired their own transformational

leader to modernize their educational system for boys and girls. Forward thinking, the towns brought in outsiders for

the change but did not anticipate the political winds changing on them. Regardless the educational foundations

instilled by these leaders may have helped those displaced to find the firm footing they needed in new lands with new opportunities.

The story told me much about the fears and hopes of the people then in Develi.

This time I wanted to explore

Develi in person to see if the culture had changed with the departure of the Armenians.

We started out day at Evereg’s

(Everek’s) Surp Toros church and accompanying Mesrobian school. Surp Toros had been the newly renovated church

in the early 20th century of the richer Evereg community, enjoyed only for a few years before being lost in 1915. Both

the church and school were confiscated by the state. The church was used a warehouse for many years and in 1978 was

converted to a mosque, the Asagi Everek Fatih Camii. Before entering we walked entirely around the whole complex.

Since 2000 the streets nearby now have also been renovated much and the storefronts had all been given an uplift. In

fact much of the old neighborhood had new construction. It was pretty but the old charm and architecture of the community

was being lost. The attached Mesrobian school was once again a primary school, the Develi Îstiklal Îlkokulu,

with a nice playground and basketball court.

The mosque was empty upon entering and we followed local traditions

with respect for this holy site. This mosque had been undergoing renovation in 2000 and old Christian frescoes were

found at the time. In Islamic tradition display of human images are forbidden and the frescoes were soon covered up

again. There was a plywood board over the fresco I had seen in 2000 this time, however it was screwed shut. This

house of prayer was quite large which gave me a perspective that the Evereg Armenian community had been large and quite wealthy.

Prayers said, we said goodbye.

We walked the street to find the Yalçin home, home of the last Armenians

in Develi. Agop and Boghos were the two brothers who had built the two homes connected to one another. Overtime

the house passed onto the brothers’ relatives, the Yalçin family, with the distinction of Vartkes Yalçin

being the last Armenian in Develi. On this day we saw a young couple in wedding outfits in front of the beautiful Yalçin

home posing for pictures. They graciously posed for me when I asked their permission to take a picture. I assume

they understood the beauty of the site given it’s unique Develi architecture. They were beginning a new life and

family in Develi. They waved back and left with their families, smiling away. We

moved on, this time to find Fenesse, where my grandparents were born. This proved more difficult though more rewarding

in other ways. Using the map provided by the Hrant Dink Foundation we walked the streets until we found ourselves at

the ruins of Fenesse’s Surp Toros church. https://hrantdink.org/.../article/1403/Develi_Raporu_new.pdf

A local guide then took me to the old stores of Armenian merchants, including the shoe repair shops and leather merchants,

part of my ancestry. He would point out each store and the Armenian family it belonged to, much to the bewilderment

of the current occupants who were either carrying on the same trade or had set up one of the many eateries in the area.

Kurtumburt, a savory stew made of cracked wheat, onions, dried meat, and spices, was still a local favorite,

though it was meant to be eaten in the winter, not a hot summer day as today. He then took me to a place

I had never heard about in my circle nor had seen previously in Armenian churches, namely the cave church of Surp Asdvadzadzin

(Holy Mother of God) in the Îlibe neighborhood. I was unable to find much information beyond that in Hrant Dink’s

book which professed the church was was likely established in the 17th century from Armenians settling here from Hadjin but

indicates it may have been an older church before—likely an abandoned Greek cave church. This cave church was

in utter ruins with a missing dome. Trash and ruins were all around. It wasn’t clear when this church was finally

abandoned but given the graffiti, it may have been in the early 20th century. This was a mystery waiting to be solved

though the damage seen may see this site no more soon. We stood at the center of this lost vast cave church with the

local guide. All of us got emotional for that moment as we felt the void together.

We ended the tour at the Develi Armenian cemetery that had been co-opted by the municipality for a playground park

and religious center. Through it ran a river, dry today, towards Chomaklu, another Armenian town a distance away.

I had written about Chomaklu in the past and there it was in the distance. https://www.researchgate.net/.../232355743_From_Charles...

The local guide recalled when the construction started and the cemetery moved to Istanbul in 1968. I

didn’t see any remnant Kachkars and no mention was made as to what happened to them. The Armenian community had moved

on and it’s history almost erased but for us telling such stories. The local guide himself reminded me of the steely Develi men I had witnessed as

I was growing up. He stood like a rock yet he was transparent and empathic with his narrative. He was welcoming

of us. We all hugged one another in tears. We thanked the local guide for his time and drove away. Echos of the

culture survived though it would have been a richer story had both my grandparents been standing there welcoming me home. Such

a tour is a complex and overwhelming journey, one that will take a long time to process. Develi encapsulated the experience for me once again, since

my first visit 22 years ago. I suspect it will not

be my last.

|

|

The

Evereg-Fenesse Mesrobian-Roupinian Educational Society is celebrating its 125th Anniversary, on September 3, 4, and 5, 2004

(Labor Day weekend), during its 17th Triennial International Convention at the Sheraton Universal Hotel.

One would

wonder why young, modern, educated Diaspora born Armenians would dedicate themselves to propagate this "old country"

organization, and maintain its ancestral traditions with the same awe and affiliation as their immigrant parents and grandparents?

Is it in respect or nostalgia of our childhood memories at hyrenagitz (compatriotic) picnics and dances, or of our parents'

and grandparents' dedication to safeguard old traditions and history, or simply fascination of the mystery of its long abiding

spirit in our veins? For a daughter of Everegtsi mother and Fenessetsi father, asked to write about the history and growth

of this organization, unfolding the mystery revealed a culture deep in tradition and its relentless urge for education.

Starting from its geography, its history and legends, to its inception in the diaspora, Evereg-Fenesse presents the

magical mystery of faith and survival of all Armenians. Here is Our Story.

Geography & History

Evereg

is located south of Ceasaria, separated by Erjias Lehr (Arkeos as the Greeks called it), the highest mountain of the region,

covered always with snow. It is believed that Noah's Ark had first hit this mountain and the Nahabed having said, "Arachinnen

eh ahs," his words had been converted into "Erjias." Before the Turkish expansion, in the years around 1285,

Evereg had been inhabited by Greeks who had built towers on the mountain and waterways down to the towns. It was conquered

by Turkish generals Dev Ali, Kheder Elias, and Sheikh Ali, and all its Greek inhabitants massacred.

Dev Ali's followers

settled on the mountain, taking over the towers and its waters, calling the town Develi. When war was over, skilled workers

were needed for rebuilding. Armenians, being known for their skills, came and settled there, but half an hour south of Develi,

in the valley where the Greeks had built a church and a waterway running down to it from the mountain. The church had been

destroyed, but the water was available. The Turks settled on the south of that waterway. The Armenians settled on the northside,

expanding later over its hills to the other side. Armenian immigrants coming from different regions were identified by their

names; for example, those from Persia were called Barsamenk, from Tehran, Tarkhanenk, from Tomarza, Domartsook. These Armenians

co-existed peacefully with the Turks, free to practice their religion, and living on gardening and commerce.

Two

hundred years later, Armenian immigrants from Konya came to settle above the hills where the Turks' homes ended, calling it

Fenesse. So the two towns of Evereg and Fenesse, although near each other (about a 10-minute walk) were separated by Turks.

Both Evereg and Fenesse prided on highly skilled craftsmen: ironsmith, cobbler, carpenter, hairdresser, tailor, weaver, etc.

Each had its own "shooga" with many shops and stores. Each had its own church, both named St. Toros, with their

adjacent schools Evereg-Mesrobian School, and Fenesse-Roupinian School.

Origins of the Organization

The Evereg

Fenesse Farmers Union was first formed in 1861 in Istanbul to help compatriots in their region. Founded and chaired by Garabed

Panossian and Kevork Kelejian( a "gesaratsi"), it gathered 300 members of cobblers, painters, "chalmale, shalvarle,"

poor people who had come to seek work in Istanbul. The union rented two restaurants and opened one tobacco store, collecting

donations - "passing a hat at the restaurant." Six months later, it had raised 28,000 ghroosh, for the towns of

Evereg and Fenesse. This union dissolved later.

During 1870's, when a general movement among the Armenians in Istanbul

aimed at elevating the standards of education in Armenian schools throughout Turkey, the Everegtsis and Fenessetsis separately

raised funds and sent qualified teachers to their homeland. Thus in 1878, were founded the Evereg-Mesrobian and Fenesse Roupinian

Educational societies, named after the schools in these two towns.

With many Everegtsis and Fenessetsis escaping

the growing strife in Turkey and moving to America, Evereg-Mesrobian was founded again in New York on October 1, 1906, extending

chapters later to other states. Many of those chapters later dissolved except for Detroit which kept sending help to its school

in Turkey till 1914. The society then sent money to its chapter in Beirut to distribute to needy emigrant families. It also

provided tuition support to elementary school students of Everegtsi or Fenessetsi descent who attended the AGBU Armenian school

in Detroit and to colleges in Michigan. "When we came to America in 1928 with my husband, there were two societies, Evereg

and Fenesse, but we attended each other's activities," explained 92-year-old Mrs. Nercessian, wife of Nercess Nercessian,

a long time secretary of the society.

When all Armenians from New York and Michigan went to California, they started

working together and suggested joining the societies. One reason, Mrs. Nercessian explained, was that as most Everegtsi and

Fenessetsi families had intermarried, the funds received from each society by their members were being duplicated. Considering

this and the fact that these two communities had lived side by side and shared the joys and sorrows of life together as one

community, the need of a merger was felt more and more strongly. Therefore, on April 17, 1955, authorized representatives

of the Mesrobian and Roupinian Associations met in New York and signed an Agreement of Unification, drawing a constitution

and by laws, which was ratified at a joint convention held on September 1, 1956.

The joint Evereg-Fenesse Mesrobian-Roupinian

Educational Society still stands to this day in many chapters in Detroit, New York, Los Angeles, and Beirut, continuing to

raise funds and supporting Armenian education and the traditions of the culture.

Evereg-Fenesse Educational Society

Celebrates 125th Anniversary on Labor Day

By Mireille Kalfayan

California Courier Online, July 29, 2004

Additional information:

Krikorian, Aleksan. Evereg-Fenesse: Its Armenian History and Traditions. Detroit, MI: Evereg-Fenesse

Mesrobian-Roupinian Educational Society, 1990. 186 pp.

|

|

|

|

|

|